Understanding user authentication for web apps

Understanding and implementing authentication from the ground up, for both vanilla JS and React/NextJS apps.

User authentication is a part of any moderately complex web application. Whether you’re building the next Twitter or a single-feature SaaS, it is important to get user authentication right. Without proper authentication services in place, you risk violating the privacy of your users by leaking confidential information to the public or other users.

In this post, we shall learn user authentication from first principles, and will go through a basic implementation step-by-step.

What’s authentication?

Let’s set the premise by getting the basics right. Your user authentication service is what keeps your user’s data private and secure from the public, or potential malicious actors. Imagine your data as being a house, your auth page being a door, your authentication service being the lock, and the user’s secrets (password or OAuth token) as the key to that lock.

What are the ways a user can authenticate?

There are primarily two user authentication methods:

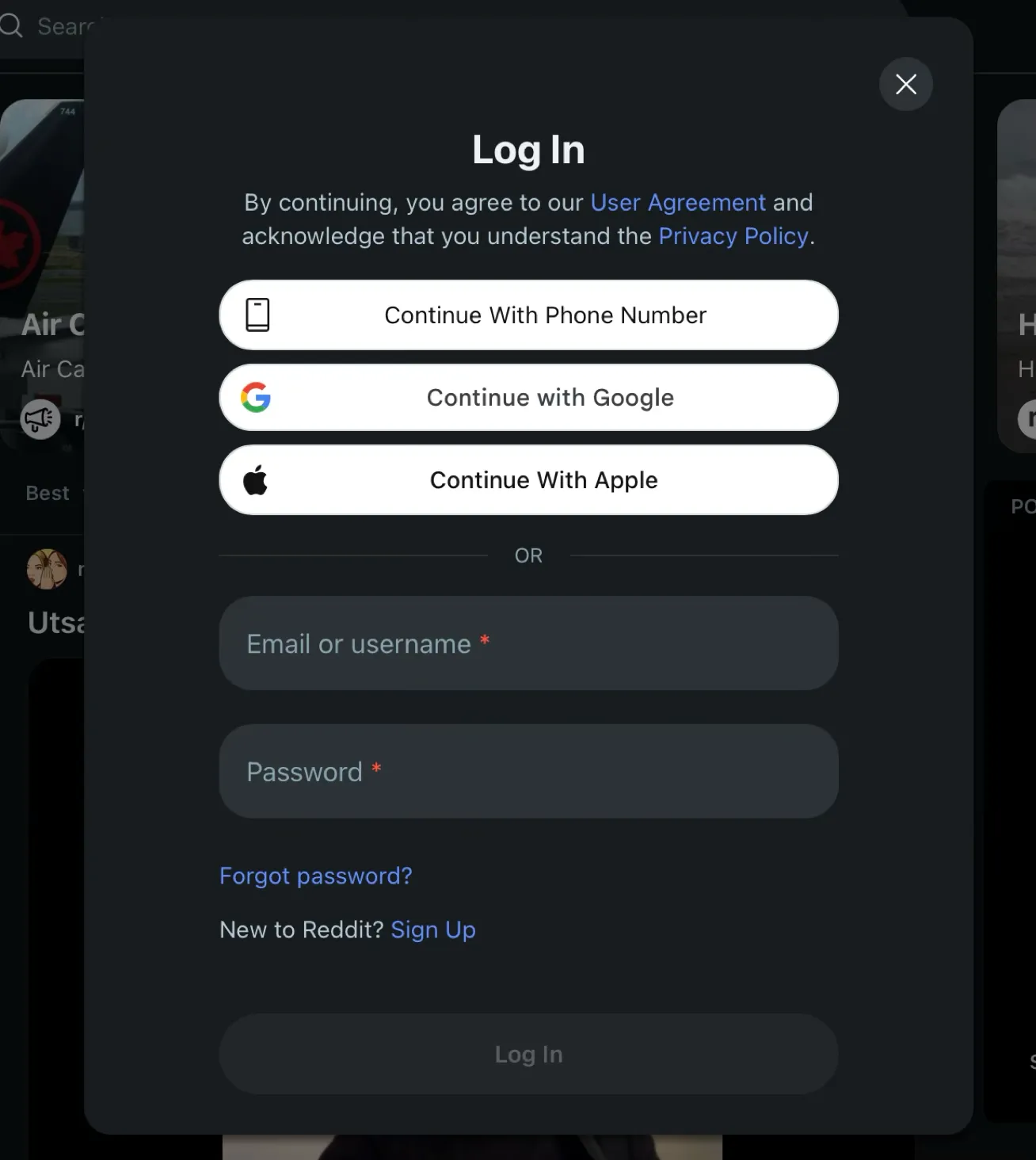

- Creating new authentication secrets: Username/email + password

- Using existing authentication secrets: OAuth

We’ll go through both here, along with relevant code examples.

Email + Password authentication

We will start with email and password authentication because conceptually it is the simplest, and it has been used since the dawn of time (or the internet, whichever came first).

To get started, here’s the usual flow of an email-password authentication system:

- User enters email and password into a login form

- The browser sends this data to the server

- The server requests the database to fetch the password for the particular email

- The server matches the password stored in the database with the password entered by the user

- If everything goes right, the server sends a response back to the browser with the relevant user information (name, IDs, etc.)

In production applications, it is malpractice to store user passwords in plaintext in databases. We usually hash them with a cryptographic algorithm (look into bcrypt) and store that hash in the database. The server, in turn, compares the hash generated by the user-provided password and the hash already stored in the database.

If you have implemented this far, then congrats for getting the basics correct! But wait, what happens when you refresh the page? Or close and reopen the browser tab? Or move to a different page within the app? Alas, you are logged out again!

This happens because you didn’t set up any mechanism by which the browser can remember you. If you think the server should have remembered that you had already logged in, then let me introduce you to the HTTP protocol. The HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the protocol underneath all of your browser-server communication. Think of it like the mailman who delivers your mail to your great-grandparents who are still using mail. And much like the mailman, HTTP does not have any memory about what mail it had delivered before transferring the current mail at hand. In the lingo, we call HTTP stateless, in the sense that it is not aware of the state of the communication; it just plays the role of a mailman.

Therefore, you need a way to incorporate state (or memory) into your communications. You do this with the help of cookies. If you’ve never heard of browser cookies, here are the things that should get you up and running:

- They are key-value pairs stored in your browser

- They are set by your server using HTTP headers

- They are sent with every request from your browser to your server

- You can delete them anytime from your browser

Session

With cookies and some simple logic, we can create a Session for when a user successfully completes the authentication process. Since cookies are stored in the browser (and thus, on your SSD/HDD), we can persist the authentication state of the user by encoding that information into a cookie. Here’s the basic flow of creating a session with cookies:

- User completes authentication

- A cookie is generated (a key-value pair like “MyAppSession”:“1234” where “1234” is some identifier for the user/session - more on this later)

- The cookie is sent to the server with every subsequent request from the browser

- The server reads the user/session identifier from the cookie

- The server sends the information appropriate for that user/session to the browser (as requested by the browser)

- When the user signs out, we simply delete the cookie from the browser

What do I store in a cookie?

The value for a cookie must be a string. You can either simply store a number or UUID string for your userId or you can store an object by converting it to a JWT string. The latter is the recommended and more secure way of doing it.

When it comes to what exactly to store in a cookie, you have two primary choices:

- Do not store sessions on a database

- Store sessions on a database

We’ll discuss both here. Let’s start with the first one, which is simpler and easier to get started with.

1. Without persisting session data in a database

When you’re not persisting session data of a user in a database, you usually put a userId or any other unique identifier for your user and an expiresAt parameter in your cookie. The latter stores the expiry date for the cookie—beyond which the server won’t validate the cookie and won’t consider the user as logged in. It is common practice to update the expiresAt value to a further date every time a user logs into your app.

Libraries like jose are used to encrypt and decrypt objects into and from JWTs.

import { jwtVerify, SignJWT } from 'jose'

/*

Example function for encrypting a "payload"

(the cookie contents) into a JWT

*/

export async function encrypt(payload: SessionPayload) {

return new SignJWT(payload)

.setProtectedHeader({ alg: 'HS256' })

.setIssuedAt()

.setExpirationTime('7d')

.sign(encodedKey)

}

// Turning JWT into JavaScript object

export async function decrypt(session: string | undefined = '') {

const { payload } = await jwtVerify(session, encodedKey, {

algorithms: ['HS256']

})

return payload

}

// Creating a session JWT

export async function createSession(userId: number) {

const expiresAt = new Date(Date.now() + 7 * 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000) // 7 days

const session = await encrypt({ userId, expiresAt })

const cookieStore = await cookies()

// Setting the cookie for the browser (this is a NextJS feature)

cookieStore.set('YourAppSession', session, {

httpOnly: true,

expires: expiresAt,

sameSite: 'lax',

path: '/'

})

}It is important that you note and understand the cookie options. In a production app, you should set the secure parameter to true. If you are not sure what these mean, look them up using an LLM/search engine of your choice or watch this video.

httpOnly: true,

expires: expiresAt,

sameSite: 'lax',

path: '/'When a user successfully completes the authentication process, the createSession function is invoked on the server with the userId fetched from the database for the user. This stores a cookie on the user’s browser and marks the user as logged in.

We can also define a deleteSession function that will be invoked when a sign out request comes from the browser.

export async function deleteSession() {

const cookieStore = await cookies()

cookieStore.delete('YourAppSession')

}If you are using ExpressJS on a Node backend, you can use the res.cookie() method for setting a cookie. For other backends, please look up the appropriate method relevant to your framework of choice.

2. Persisting session data on a database

If you want to do cool stuff like tracking the number and/or IP addresses of devices a user has logged in from or would like to restrict the number of devices a user can log in from, you should be looking into storing your user session info in a database.

This begins with defining a database schema for your session, and it looks something like this:

CREATE TABLE Session (

id TEXT PRIMARY KEY,

expiresAt DATETIME NOT NULL,

userId TEXT NOT NULL,

accessToken TEXT,

-- and more ...

FOREIGN KEY (userId) REFERENCES "User"(id) ON DELETE CASCADE

);The flow for database persisted session mechanism works like this:

- User signs into your app

- A session object is created with the

userId, IP address or whatever you might want to store about the session and is inserted into the database. - You get the

idfor the newly created session from your database - You encrypt this

idas a JWT or into a hash that requires a private key to decrypt - You store this encrypted

idinto the browser cookie - When the browser requests for something, this encrypted cookie is sent with the request and the following takes place:

- It is decrypted to get the

id - The

idis used to fetch the rest of the session details from the database - The

userIdfrom the session object is used to send relevant data back to the browser

- It is decrypted to get the

As you might have noticed, this process is more resource-intensive on the server than the previous one. This does come with the trade-off of more security versus the database-less approach.

OAuth

OAuth or Open Authorization is one of the modern approaches to user authentication. Here, instead of having the user enter their details on your website, you re-use already available user data on other popular websites. Although anyone can provide an OAuth service, websites and apps usually use OAuth data from popular services like Facebook, X or GitHub. Implementing OAuth might be an easier way to get started with implementing authentication for your app.

I’ll be using GitHub OAuth for my examples in this post. The underlying concepts can be applied to any other OAuth service of your choice.

The OAuth flow looks like this:

- User presses “Sign in with GitHub”

- User is redirected to the url

https://github.com/login/oauth/authorizewith the followng parameters:client_id: You obtain this from GitHub while registering the GitHub OAuth appredirect_uri: The URL where GitHub should send your users to once they approve the sign instate: A random string that is used to prevent CSRF attacks

So, the entire URL looks like this:

https://github.com/login/oauth/authorize?client_id=<YOUR_CLIENT_ID>?redirect_uri=https://yourapp.com/oauth?state=<YOUR_RANDOM_STATE>Next, GitHub sends the user back to the URL you specified in the redirect_uri with a code parameter.

https://yourapp.com/oauth?code=<SET_BY_GITHUB>We use this code to receive an access_token with a POST request to https://github.com/login/oauth/access_token with the following parameters:

client_id: Obtained while registering the OAuth app, as mentioned earlierclient_secret: Also obtained from the GitHub OAuth app dashboardredirect_uri: The same as beforecode: As received in the URL parameterstate: This must be the samestatestring as before

So, all in all, the request looks like this:

POST https://github.com/login/oauth/access_token?client_id=<YOUR_CLIENT_ID>?client_secret=<YOUR_CLIENT_SECRET>?code=<THE_CODE>?state=<THE_STATE_FROM_BEFORE>?redirect_uri=https://yourapp.com/oauthThis returns a JSON response like this:

{

"access_token": "gho_16C7e42F292c6912E7710c838347Ae178B4a",

"token_type": "bearer"

//...more

}This access_token is your key to obtaining user information from GitHub servers. Next, we use this token to make API calls to the URL https://api.github.com/user. This returns us various user details like name, username, email, avatarURL etc. We extract the things that we need for our app from this.

const { email, name } = await (

await fetch('https://api.github.com/user', {

headers: {

Authorization: `Bearer ${access_token}`

}

})

).json()We create a new user or retrieve an old user from our database using this information and create a session just like before, thus completing our authentication process.

Feel free to reach out via any channel: amkhrjee.in